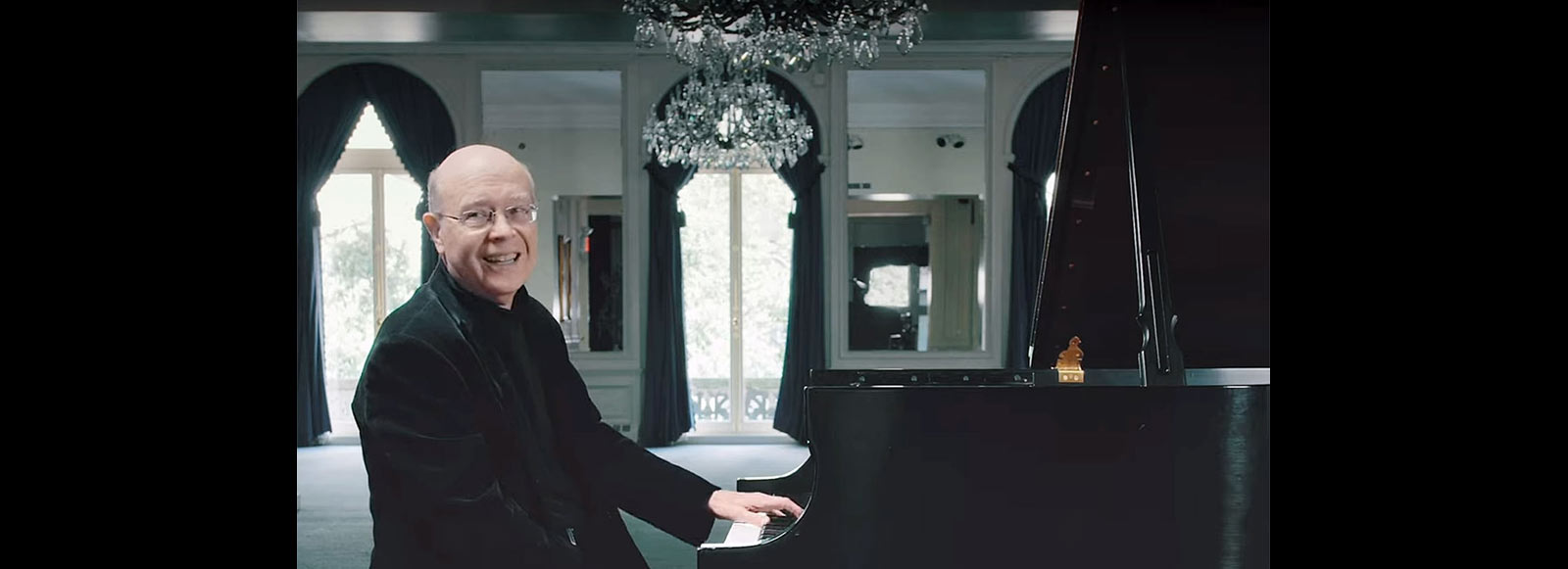

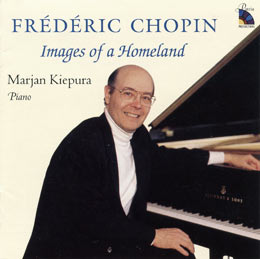

Chopin Recordings by Marjan Kiepura

CD: "Images of a Homeland"

Individual CD tracks are described below by Marjan Kiepura.

YouTube links for each track are provided or listen to the entire CD on YouTube.

Read more about Chopin's history below from the copy included in the CD.

1. Mazurka In G Minor, Op. 24, No.1: 1834-5

With some 230 works composed by Chopin, there were approximately 200 written for solo piano. Of those, there are 58 published mazurkas. The form was of enormous importance to him and he composed mazurkas from the beginning of his musical life until the very end (his last work was in fact a mazurka). The genius of Chopin, especially in his mazurkas, was his mastery to fit in an extraordinary amount of music into a very short space with never a note wasted. This is evident in this piece and numerous others throughout the genre.

Listen to the CD track →

Watch Performance with Introduction →

2. Mazurka in C Major, Op. 24, No.2: 1834-5

A sister work to the above, Chopin shows the directness with which he communicated his ideas. Following a chordal introduction reminiscent of Polish dance themes, this mazurka moves quickly through several different musical ideas of considerable refinement, again, in a relatively short space of time.

Listen to the CD track →

3. Mazurka in C-sharp Minor, Op. 6, No.2: 1830-1

Opus 6 and 7 were the first two sets of mazurkas which he chose to publish, even though he had already started composing them earlier. Chopin stressed to his publishers that his mazurkas were "not for dancing." With the elegance of this piece, Chopin had already redefined the mazurka as a dance form.

Listen to the CD track →

Watch Performance with Introduction →

4. Mazurka in A Minor, Op. 68, No.2: 1827

An early work, it was one of his first in the mazurka genre composed when he was but 17 years old. It is in a way crucial as it outlines already mature musical ideas built into a simply constructed piece. The mood created evokes the quiet soulfulness of a "kuyawiak" or slower dance. Chopin would return numerous times to the kuyawiak in his mazurkas.

Listen to the CD track →

Watch Performance with Introduction →

5. Mazurka in B-flat Major, Op. 7, No. 1: 1830-1

The five mazurkas which comprise the set of Opus 7 contrast significantly with one another. This is most evident in the three selections presented herein. This particular mazurka is said to be the most popular of them all. Its familiar tune and the all important rhythms and accents are a signature among the mazurkas, and a great favorite in the concert hall.

Listen to the CD track →

Watch Performance with Introduction →

6. Waltz in F Minor, Op. 70, No. 2: 1841

During Chopin's time, the development of the waltz was revolutionary. People actually held each other while dancing, as with the waltzes by Johann Strauss and Joseph Lanner. When Chopin turned to the waltz, composing some 20 in all, it was clear that, like his mazurkas, his waltzes were for the soul, not the feet. This waltz is rarely programmed by itself in recitals, although Chopin is said to have often played it for his friends. He was fastidious in applying performance indications to his music. The "tempo giusto" marking is poignant for this waltz - a piece which should be heard more often.

Listen to the CD track →

7. Mazurka in F Major, Op. 68, No. 3: 1829

This early example is a true and lively "mazur," based on old Polish dances (medium in tempo). Like all mazurkas, it is in triple time, but its pronounced rhythms define this musical form. I also see this mazurka to contain polonaise-like features. Direct in its statement, it is at the same time majestic in its elegance.

Listen to the CD track →

Watch Performance with Introduction →

8. Mazurka in A-flat Major, Op. 41, No.4: I839

It is said that nearly half of Chopin's works were composed in Nohant, George Sand's country home in central France, where he seemed to find peace in the rural setting, away from the bustle and commitments of Paris. This piece was written there and evokes a spring-like demeanor, where flowers are in bloom and the trials of winter have been left behind.

Listen to the CD track →

9. Mazurka in B Minor, Op. 33, No. 4: 1837-8

Scholars contend that Chopin's so-called "mature" period of composing occurred after 1831, when he had reached his twenties, the theory being that, by then, he had had time to develop and ripen as a composer. This can be debated. What is clear in this work, however, is that Chopin had reached a creative pinnacle in the development of his mazurkas. By now, he was established in Paris, romantically involved with George Sand and all which her world involved, yet at the same time, feeling the growing anguish of the separation from his homeland. Among the longest of his mazurkas, it adopts a broader approach to the dance form-not owing strictly to its length, but more to its declaration. The concept is operatic in both its initial statement as well as in its later development. Stentorian, yet at the same time lyrical, it almost anticipates the arias of Puccini. Among his mazurkas, this is an epic composition.

Listen to the CD track →

10. Waltz in A-flat Major, Op. 69, No. 1: 1835

This famous waltz is accompanied by the equally famous story of Maria Wodzinska, a childhood acquaintance. After Chopin left Poland, they corresponded, and then became reacquainted during a holiday in Dresden in September of 1835 where Maria, now in her teens, had traveled with her family. The early childhood friendship blossomed into serious intentions on Chopin's part. However, Maria's family rejected his intentions owing to what they unfairly considered to be not only his fast lifestyle of parties and late nights in Paris, but more frankly, the uncertainty of life with an aspiring composer. They wanted their daughter to marry "royalty" which she later did, most unhappily. When they parted, Chopin gave her this waltz. She later named it "L' Adieu." Shorrly after this episode, Chopin's initial friendship with George Sand intensified.

Listen to the CD track →

Watch Performance with Introduction →

11. Nocturne in E-flat Major, Op. 9, No. 2: 1830-1

Chopin's fondness for Italian opera is said to be evident in all of his nocturnes, the melody line evoking the Bel Canto or singing style, which he often stressed in his teachings to his students. The most familiar among the nocturnes, this is yet another genre which Chopin championed, following the basic form established earlier by the Irish composer and pianist, John Field.

This work also has a historic connection to Maria Wodzmska, referred to above. At the same time as he composed the Waltz, Op. 69, No. I, he also wrote the first few bars of this nocturne on a card to Maria. On the other side of the card he wrote, "Soyez heureuse" -"Be happy."

Listen to the CD track →

Watch Performance with Introduction →

12. Polonaise in A Major, Op. 40, No. 1 "Military": 1838-9

Of his sixteen published polonaises, Chopin's youthful forays in the genre were somewhat ornate, largely as a result of the teaching style of the time. Chopin actually stopped composing polonaises for about 5 years. His return to the form, after settling in Paris, had a depth and verve not experienced before. Starting with the Opus 26 polonaises onward, Chopin's passion about his homeland reached its zenith. Once again, speaking through his music, his polonaises would evoke either the gloom or the triumph of Poland. In the case of this famous "Military" polonaise, it was his very personal and unabashed declaration of glory and victory.

Listen to the CD track →

13. Waltz in A Minor, Op. 34, No. 2: 1831

Said to have been Chopin's very favorite among all his waltzes, this is also akin to the slower mazurkas in its style. Strangely, however, this waltz is noted by publishers as "Grande Valse Brillante" which would denote a piece of sweeping virtuosity. The title is appropriate, not for its virtuosity, but rather for its artistic depth.

Listen to the CD track →

14. Mazurka in C Major, Op. 7, No. 5: 1830-1

This is an "oberek," a light-hearted, faststyle dance, characterized by a throbbing bass accompaniment. Chopin's friends often said of him that he should have been an actor and comic, owing to his ability to mimic and act out events in a spirited and comical way. For me, the flavor of this mazurka reveals this side of his personality.

Listen to the CD track →

15. Mazurka in F Minor, Op. 7, No. 3: 1830-1

This piece contrasts the lively Op. 7, No. 1 and the Op. 7, No. 5 in every manner and form. Its mood seems to denote the nostalgia which Chopin often felt of being separated from his homeland, and the recurring Polishness with which he expresses himself. Here we experience the Polish term "zal" as it applies to much of Chopin's music-smiling through tears. But smiling is the operative term.

Listen to the CD track →

16. Mazurka in A-flat Major, Op. 50, No.2: 1841-2

This piece again falls into the category of mazurkas which scholars believe became expansive and thick textured over time. Although a light-hearted work evoking a much different mood from the prior mazurka, Chopin guides us through several musical ideas. One is always aware that Chopin is at the very peak of his communicative powers.

Listen to the CD track →

Watch Performance with Introduction →

17. Mazurka in G Minor, Op. 67, No.2: 1848-9

This piece was in fact the last piece Chopin composed in August of 1849. Chopin passed away that October. It is often thought that his very last composition was the Op. 68, No. 4 mazurka but that has been disproved. That mazurka was composed three years earlier in 1846 and found in the diary of the famous cellist and acquaintance of Chopin, Auguste Franchomme. Despite its obvious sadness, Chopin found a lighter moment as observed in the middle section- not an uncommon trait of his style.

Listen to the CD track →

18. Prelude in D-flat Major, Op. 28, No. 15 "Raindrop": 1836-38

This is the longest in the collection of the Op. 28 Preludes and one of the most familiar works in all of piano repertoire. It is a stand-alone recital piece having an identifiable beginning, middle and concluding section, unlike many of the other preludes which are short by comparison. It was composed during an unhappy time of solitude and ill health when Chopin and George Sand were in Valldemosa, Mallorca. An anecdote coming from George Sand's diary indicated that in the middle section Chopin heard the monks chanting. But the monastery was abandoned. He heard it in his imagination. As a footnote, the name "Raindrop" came from George Sand as it reminded her of the rainstorms in Valldemosa. Chopin did not like nicknames attached to his works. Nevertheless, it remains to this day.

Listen to the CD track →

Watch Performance with Introduction →

19. Mazurka in C Major, Op. 68, No. 1: 1829

Although one of his first mazurkas, the brisk introductory chords here, with their pronounced rhythm, impart the remarkable way in which Chopin would introduce his Polishness, particularly in the mazurkas. The resulting dance-like spirit is a critical structural foundation, and a recurrent trait in these works.

Listen to the CD track →

20. Mazurka in A Minor, Op. 17, No. 4: 1832-3

More like a nocturne or fantasy than mazurka, the rhythmic accents are implied rather than obvious. "Smiling through tears," or Zal, is poignant here.

This piece reminds me of a letter Chopin wrote while in self-imposed exile. Describing his life in a moment of loneliness to a friend, he wrote: " ...I get back about ten or eleven, never later than twelve. I play, cry, read, stare, laugh, get into bed, blow the candle out and dream about home."

Remarkably, this work contains a degree of chromaticism and dissonance anticipating modern modes of composition a hundred years hence. Chopin influenced most composers of piano works who followed him, well into the 20th century, including, for example, Debussy, Rachmaninoff and Scriabin.

This mazurka is an important contribution to the genre. It further illustrates that his collection of mazurkas were not only a dominant aspect of his output, but a monument to his legacy.

Listen to the CD track →

Watch Performance with Introduction →

Copyright © Marjan Kiepura, June 2000

"Images of a Homeland" - Liner Notes

With this compact disc recital, it has been my goal to illuminate specific aspects of the genius of Frederic Chopin. It is my intent to observe Chopin as a person deeply affected by influences, which historians collectively acknowledge as reflecting thoughts of his homeland and the essence of his heritage-the Polish earth. This resulted in unique piano works which mirror his deeply held memories of Poland and the distinctive flavor and rhythms of her music. It was through Chopin's gift, however, that these musical forms were transformed into something totally original and extraordinary.

Frederic Chopin was above all a creator and visionary. Sensitive and enigmatic, he had an extraordinary musical intuition whose style and explorations would alter the course of musical composition, the possibilities of interpretations at the piano, and create a level of innovation which was unique in the world.

Born in 1810 in the town of Zelazowa Wola, near Warsaw, Chopin spent his formative years in Poland. With his French-born father, a tutor of the French language to Polish aristocrats, and his Polish mother, he grew up in a family where education was stressed. The Chopins had four children. Frederic was their only son. His early musical education already showed promise. But it was his childhood experiences in Poland that had a lasting effect on his soul and spirit. Images of the Polish countryside and peasants dancing and singing to folk tunes with pronounced rhythms, left an indelible mark on him.

As he rapidly developed as an artist, Chopin realized that, at least for a time, he would have to seek exposure in Europe's other musical capitals. Vienna provided his first significant venue outside of Poland both as a pianist and composer. It was also here that he composed several important works, including the Opus 6 and Opus 7 Mazurkas and the Nocturne in E-flat, Opus 9, No. 2 presented on this recording.

The city of paramount cultural significance at the time, however, was Paris. When Chopin finally arrived there in 1831 aged 21, he joined such illustrious company as Victor Hugo, Heinrich H eine, Eugene Delacroix, Honore de Balzac, Franz Liszt, and, of course, several Polish poets such as Adam Mickiewicz. It was the perfect environment for a young composer of genius and it was here that he met the woman with whom he would share very important years - George Sand.

Yet, the separation from his homeland, his native language, his family and friends, and all that reminded him of the Polish earth, had a profound effect. To understand this, let us examine the historical background of Chopin's Poland.

Painting by Zofia Stryenka

Historically situated between powerful and warring nations, Poland had become reluctantly accustomed to the indignity of territorial division by her neighbors. With Napoleon's defeat ending the War of 1812, the Congress of Vienna convened in 1815 and created the so-called "Kingdom of Poland."

This was intended to give final credence to an independent Poland. Chopin was five years old at the time. The reality was that this "Kingdom" would be ruled by Czar Alexander I of Russia. With Alexander's death in 1825 came an even more repressive regime under Nicholas I.

Indeed, repression became an ever-present cloud over Poland. Chopin wanted to see Poland again. But ongoing political strife compounded by his own advancing ill health due to tuberculosis, would make his exile permanent. Chopin's separation from his homeland began to wear on him. The seeds of frustration and the flame which burned within were fertile ground for a man who expressed himself through his music. Elegant and reserved at all times, Chopin was not political as such. His passions rose to a different plane.

Frederic Chopin became the proponent of at least ten separate musical forms. He brought to each his own stamp of genius. The ballades, scherzi, sonatas, piano concerti, nocturnes, waltzes and preludes, among others, were redefined in the crucible of his individuality. It was in his mazurkas and polonaises, however, where the distinctive flavor and style of what has become known as the "Polishness" that we hear in his music, was created.

Both the mazurka and polonaise existed well before Chopin's time. However, Chopin took the basic mazurka form and transformed it to an altogether different and extraordinary level of expression and sophistication, Likewise, the polonaise, a majestic procession-like dance, became a national symbol in his hands.

The concept of "Polishness" mentioned here seems to have existed in the privacy of Chopin's mind, accentuated by his exile. But the special atmosphere of this music coupled with his use of distinct rhythms and accents with which he conveyed his musical ideas, are characteristic of this "Polishness." These compositions also became the epitome of Chopin's most passionate feelings, and at the same time, the defining spirit of a nation.

Through the friendship of Jane Wilhelmina Stirling, a Scottish lady of society, Chopin visited England and Scotland in 1848 where he gave concerts under the continuing strain of his declining health.

Returning to Paris, Frederic Chopin succumbed to his consumptive illness, passing away on October 17, 1849 at 2 AM, as if to slip quietly into the night. The world mourned the loss of a man who spoke from the depths of his soul, with a style and directness that could only be "Chopin."

"Images of a Homeland" attempts to illustrate the correlation of what was dearest to Chopin, and the music which evolved, from his earliest to his latest compositions. The "Polishness" of his mazurkas, his unspoken patriotism in the polonaise, the solitude he felt when he drafted the Raindrop Prelude and the unrequited love for a young woman he had left behind in Poland (Waltz in A-flat Major, Op. 69, No. 1) with its Polish spirit intact, are extraordinary examples of an artist's profound response to that which was closest to him.

It is a significant fact that nearly half of Chopin's published solo works utilize various dance forms. Clearly, Chopin's Polish characteristics were most pronounced through these distinctive dance forms, and for him, these compositions were of great importance in his creative oeuvre. The choice of repertoire on this recording reflects that view.